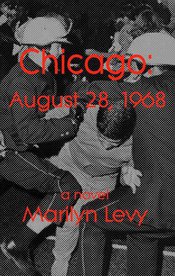

Chicago: August 28, 1968 by Marilyn Levy

Marilyn Levy’s extraordinary novel Chicago: August 28, 1968 relates what a dozen ordinary Americans experience on a single day during the Democratic National Convention and the riots outside in Grant Park. Viewed through the eyes of Levy’s varied characters—among them a teenager, a cop, an artist, a psychiatrist just back from Vietnam, a black activist, and a dying woman—Chicago: August 28, 1968 explores the consciousness of people thrown together during this crisis. The novel goes beyond politics, however, and sheds light on the complex relationships between human beings and on the consequences of their interactions—of the effects that parents have on children, of words said and unsaid, of emotions restrained or allowed to explode, of corrosive secrets. The book reveals a kaleidoscopic image of how people of many different backgrounds and ideologies survived a traumatic event that continues to reverberate even today. Marilyn Levy’s Chicago: August 28, 1968 is a novel about the recent past, but it’s also a mirror that shows us a disturbing image of our own time.

- ISBN: 978-1-932727-16-6

- Price: $16.95 (paper)

Read an Excerpt

Chapter One: Civil Rites

Becky drifted out of the apartment on a wave of her mother’s indifference. I said good-bye; I did my duty. Jesus Christ, “duty.” She laughed at herself, quickly neutralizing her mother. Then dismissed her mother altogether as she ran down the three flights of stairs worn bald by anonymous feet.

Sprinting down Bosworth towards Howard Street, she caught sight of Violet, sitting in her wheelchair, her face digesting the intense rays of the sun. Violet liked to act tough. But she seemed sad to Becky, so Becky always stopped to talk to her. Even when she was in a hurry.

“Hey, Violet.”

“Great day. Great day,” Violet said, squinting at Becky. Becky was never sure if Violet could actually see her. A white eye patch covered one blue eye, and the other eye, enlarged by a thick smudged lens, kept changing direction.

They bantered about the weather for a few minutes. “Finally, got a breeze from across the lake. Made my own swimming pool from the humidity—sittin’ in this chair. Can’t wait till August’s done with,” Violet groused, before shifting to a graphic story about the changing neighborhood.

Nodding, Becky fidgeted with her sign. What the hell? I can wait two more minutes. Still, she had to calm every muscle in her body, straining to move on. She stared at Violet’s wandering eye, trying to keep track of the story she was telling. She couldn’t concentrate. Just listen to her. Listen. She’s stuck in this spot forever. Some day, I’ll leave, and I won’t look back, Becky promised herself. Then, even though she didn’t mean to, she grinned.

“Important day,” Violet said. “Going downtown, I bet.”

“How’d you know?”

Violet picked up her transistor radio and waved it at Becky. “I wasn’t always sittin’ in a wheelchair.”

Becky felt a wash of shame flood her body and settle into her knees.

“I used to do what you’re doing.” Violet nodded at Becky’s sign. “Used to picket, used to carry signs like that. Ever hear about the sweat shops in New York?”

Becky wrinkled her forehead as if she were trying to retrieve a lost memory.

“Go kick ass for me.”

Becky laughed; then she leaned down and kissed Violet on the little rivers of her age-spotted cheek. Which until that moment had always kind of revolted her.

Sitting on the El as it clattered away from Howard Street towards the Loop, Becky wondered why it had never occurred to her that Violet must have had a life before she got old and useless. It seemed as if Violet had always been old. Like there was no history before I was born, she thought with a start. I guess I can imagine my father being my age. He’s still sort of a kid. But my mom—she was always forty. Or a hundred. Why the hell did he marry her, anyway? She looked sexy—in those pictures of her before I was born. I can’t imagine her actually having sex. “Yuk,” Becky said out loud.

She squirmed as a flash of embarrassment lit her face. Then she quickly stared out the window at laundry flapping at her from utility porches, as the El zipped past decaying apartment buildings in Uptown. She shut out the image of her father. I was looking for something in a drawer of the knotty pine secretary—that was usually locked. Wow! Where did that thought come from? What was I looking for? Probably adoption papers to prove that that woman couldn’t possibly have given birth to me. Becky could see the box now—with a maroon velvet ribbon around it. Must have found ten or fifteen anniversary poems my dad wrote. She tried to recall one of them, but she couldn’t. What she did recall were the feelings she’d had after reading all of them. Sad. Empty. Angry. He was almost begging for her love. It was pathetic. She shook her head to shake off the memory. There was a gap between what she knew and what she chose not to know about her parents. And she wanted to keep it that way.

By the time the El had shimmied underground and transformed into a subway, Becky had banished her childhood memories and was standing at attention in front of the automatic doors, ready to leap out the moment it screeched to a halt. Shaking from side to side, the train slowed, then jerked to a stop just long enough to disgorge a few passengers from each of the exits. She spun out the door and whirled through the turnstile, her slender, wiry body barely touching it. Avoiding the escalator, she took the concrete steps two at a time.

Carrying her anti-war poster, she cut through Sears, hardly noticing the vacuum cleaner salesmen lazily strolling among the merchandise. Then she crossed Wabash under the El tracks and entered the back door of the cavernous, multi-story building that houses Roosevelt University. She took the same route three times a week during fall and winter semesters. Now the nearly empty building felt a little strange and unfamiliar. Her footsteps echoed as she rushed through the back entrance and headed towards the front doors. I’m here; I’m here; I’m here, she repeated to the rhythm of her footsteps. She pushed open the front door facing Michigan Avenue. Across the street was her destination—Grant Park.

She shoved the revolving door with her right hand and quickly squeezed through the narrow opening, too impatient to wait for it to expand and allow her an easy exit.

For a moment, she thought about what had happened in Lincoln Park the night before. She saw cops chasing them, beating up anyone who crossed their path. For a moment, she felt scared again. But she forced the moment to pass, telling herself that the cops wouldn’t bash heads in broad daylight.

Inching her way through the swarm already milling around the grassy areas, she noticed a group had congregated nearby. She edged closer. A black guy, dressed like some down-and-out preacher, was elevated on a scruffy wooden platform-like cart on wheels. The platform was tethered to a donkey. She couldn’t hear exactly what he was saying, didn’t know who he was, and didn’t recognize anyone. But she didn’t feel alone; she felt elated. I’m part of this, she kept saying to herself, as if she couldn’t quite believe that she really was.

“Fuckin’ A, man,” the stranger standing next to her said. “The old guy might be a pacifist, but I ain’t goin’ down without a fight.”

Becky turned to him. “Me neither. I hate the whole fucking establishment.”

“Neat sign,” the stranger said.

Becky nodded, pleased that he’d noticed. But at the same time, she heard her mother’s voice. “You’re always so contrary,” her mother had murmured yesterday when Becky was working on the poster. Looking up from the sign, Becky had felt a momentary stab in her gut; then she’d shrugged it off and continued sloshing red paint on the 10x12 poster board that now spelled out MAKE LOVE, NOT WAR. “Always?” What the hell do I care what she says, anyway?

She was in Grant Park because she had to be. She could have told her mother that she was making the sign for Adam Bond, a kid she’d gone to high school with. A kid who’d died in Vietnam. But she didn’t. I’m here for him, she told herself—and for the other kids in my class who won’t ever come home again. She felt half-guilty; every nerve in her body tingled as the synapses in her brain snapped together. “I’d like to stick my sign in the faces of all those senators and congressmen who wouldn’t send their own sons to Vietnam,” she said to the stranger standing next to her.

“Or someplace even more appropriate.”

Becky laughed at the thought. But it was the kind of laughter you hear when people tell funny stories after a funeral.

Becky had trained herself to stand up for what she believed in—much easier than standing up for herself.

“Who’s the guy talking?” she asked the other demonstrator.

“Abernathy. Ralph Abernathy. He’s some kind of minister.”

Becky looked up at the Reverend and smiled. She’d brushed off religion years ago, but she felt calmed by his presence, anyway.

A familiar smell drifted past her. She glanced around. Then shifted towards the smoke. What is it about smells, she wondered. Danny’s neck, she thought suddenly. She hadn’t seen him in years. God, I dated him for months before I realized it was his Old Spice that turned me on. All that huffing and puffing and anything-but-intercourse, and what I liked best was the smell on my skin afterward.

“Been here long?”

“Balkan Sobrine,” she said. For a moment she wondered if she should initiate a flirtation. But only for a moment. Becky was intoxicated by the force of the demonstrators surrounding her. And her excitement was too strong to contain.

She stared directly at the guy smoking the pipe. She’d mastered the mess-with-me-at-your-own-peril look in order to ward off wolf-whistlers at construction sites and mumblers passing her on the street. But now, there was no hostility in her stare, just curiosity. He’s older—maybe close to thirty. Doesn’t look like the other protestors. Whoa—not even a flinch. Just smiling. The smile was a little disconcerting, but she kept staring, anyway. What’s with the jacket? It’s almost white—and linen? Probably plucked it off a hanger at Saks Fifth Avenue—a store she knew only from newspaper ads. Kind of cool, though, with the black shirt and black slacks. Also expensive. Balkan Sobrine’s probably the only thing we have in common. Too bad because he’s actually handsome in a sort of uptight Gary Cooper way.

The man drew on his Meerschaum pipe for a moment, seeming to use it more as a prop than as a source of satisfaction. “Want a puff?” he asked, offering her the stem.

She was beginning to feel almost giddy. “No thanks. I quit. But I still love the smell of it.”

“Hmm, he said, putting the pipe back into his mouth and drawing in again.

She couldn’t see his eyes behind the round, wire-rimmed sunglasses, but she knew he was staring at her. She took off her own sunglasses. The glare caused her pupils to retract to a pin- point. She liked to surprise people with her unexpectedly deep green eyes shaped like a cat’s.

“Not very.” Lowering her poster, she ran her hand down her straight, thick black hair, parted in the middle.

“You from Chicago, or did you come in for the show?”

“Chicago, but I wouldn’t exactly call it a show,” she said, now irritated at herself for stopping to talk to an outsider.

He arched one eyebrow.

“Hey man, you don’t have any idea what’s coming down, do you?”

“Guess not.”

“This isn’t a freak show.” She put her sunglasses back on. “Gotta go.”

“But I know what went down yesterday,” he said, as she picked up her poster and started walking away.

“Oh yeah? What?” she asked, challenging him. At the same time, he scared her a little. Even the smart boys from her high school had looked like hoods and had spoken like truck drivers. And Roosevelt was a commuter college, where kids like her could work part time while taking classes.

This guy with his expensive clothes and wire-rimmed glasses looks like he went to some Ivy League school, she thought. She was both annoyed and intimidated.

“Is this a test?”

“Yeah.”

“I saw a few heads busted, some people maced in Lincoln Park.” “You were there?”

“I live across the street from the park.”

“Lucky you. Did you cross the street—or just watch us from your window?”

“Actually, I just watched from my window.”

“Figured. Don’t suppose you noticed the police chasing us all the way to Old Town,” she said, trying to harness her Westside Chicago accent. Despite her irritation, the smoker, she’d noted, was accentless. He spoke with perfectly formed vowels, unlike her and her friends whose broad “a” hurled up the backs of their throats and neighed out of their noses.

“Sorry I missed that.”

“Yeah, I bet. What are you doing here, anyway?”

“Demonstrating.”

“You mean watching the demonstrators. Or maybe spying on us. Why don’t you take off that fancy jacket, lose the pipe, and pick up a sign, man? If you really want to demonstrate.”

Taking off his sunglasses, he smiled at her, a half smile that invited speculation. She watched as he wiped his glasses against his jacket leaving a smudge on the sleeve. He tucked his pipe into his jacket pocket.

She was caught off guard by the intensity of his blue eyes that seemed to mock her. Then he squinted for a moment before replacing his glasses, putting his almost arrogant self-assurance in jeopardy.

“You a McGovern fan?” she asked.

“Not really.”

“McCarthy?”

“By default. You?”

“Hardly.”

“How come?”

“Not my idea of a candidate. Too white bread. Too bourgeois.”

“Ah—you like ‘em down and dirty like Nixon. You’re a Republican in disguise.”

“Nixon!” she spat out contemptuously. Then she closed her eyes. "I don't know. I’d have voted for Bobby Kennedy if I were twenty-one and could actually vote. Yeah, she said, sighing. “I would have voted for him, hands down. But since Bobby’s gone, I’d write in Eldridge Cleaver’s name.”

“A rapist? The guy who hates ‘honkies’?”

“People change.”

“In that case, maybe I’ll vote for Nixon,” he said, grinning.

“Might as well. No difference between him and Humphrey.”

“Nixon wins the election, you’ll change your mind about that one,” he said lightly.

“Maybe.” Her attention drifted to the crowd beginning to spread out to the south.

He looked around, and then turned back to her. “So what do you think’s gonna happen?”

“Don’t know.”

“You have no idea?” he asked, pressing her. “I’m not one of the organizers, if that’s what you mean.”

She studied him carefully. “You an undercover cop?”

“Do I look like one?”

“Kind of.”

“Ah ha. No wonder I haven’t been able to buy any grass.”

“Here.” She reached into her jeans pocket and pulled out a single joint. “Have a ball.”

She turned and worked her way into the crowd to get closer to the platform and hopefully locate her friends. The flirtation had run its course. At the same time, she was keenly aware that the guy was focused on her body. She wiggled her butt inconspicuously, incorporating the wiggle into her natural gait. Then she slipped through the crowd as deftly as a ballerina.

He laughed out loud. “Hey, green eyes,” he called after her, but she’d already disappeared, leaving behind the smell of patchouli oil.

Praise for Chicago: August 28, 1968

A good novel impresses you with its artistry and insight. A great one, like Marilyn Levy’s Chicago: August 28, 1968, grabs you and doesn’t let go. You remember where you were when you read it, you forget that the characters and the scenes weren’t real (or were they?) and you think of it every time you put down another book that wasn’t quite as good—which is to say, most of them.

For those of us who lived through it, [Chicago: August 28, 1968 provides] satisfying recognition and some good insights into other perspectives. For those who did not live through it, there is a valuable history lesson.

Chicago: August 28, 1968 has been added to your shopping cart.